· By David Katznelson

Knocked Sideways by the Sound

“Records are magic acts. They’re not tricks or illusions. But those that mean the most often seem to explode into existence in front of us this very minute, without prep or precedent. As many times as we’ve heard them, we can still be knocked sideways by their impact. That’s some potent conjuring.”

So speaks one of the elder statesmen of rock journalism Gene Sculatti in the introduction of his new book, “For The Records: A Close Encounter With Pop Music.” A fellow San Francisco native, Sculatti was one of the first writers to report on the burgeoning San Francisco scene of the 60s. His article “San Francisco Bay Rock” introduced most of the world to The Family Dog, “Trips Festivals,” and all of the bands that were the foundation of the San Francisco flower-wearing sound. From then to now Sculatti has held many jobs in the industry, always following his passion for music—for as he says in pondering his motivations for writing this latest book: “It is all about the music” (he is so right).

I have read the work of Gene Sculatti for a long long time (loved the book he co-wrote: San Francisco Nights: The Psychedelic Music Trip), and got really excited when hearing that he had just come out with a new book featuring meditations around the music that helped define his life…records that “knocked him sideways by their impact.” “For The Records” does the job of adding new colors and textures to the greatest music of times past, fueled by Sculatti’s life experiences and late-night stereo-anchored insights….featuring many of the worlds most beloved songs and, more excitingly for me, tracks that I had never heard before (he put together a fantastic soundtrack for the book, available on your local streaming platform).

He was kind enough to let The Signal publish an excerpt from his new book for you all to enjoy. A true honor (thank you, Gene!). The following piece finds Sculatti digging into a window of time that would define one of the most important genres of popular music. Take it away, Gene….

THE HEART OF PRE-SOUL

By: Gene Sculatti

You can keep your James Brown.

For the most part. He’s among contemporary music’s most expressive singers (“Please, Please, Please”), and one of its most revolutionary and influential artists. The latter credit is what diminishes him for me. Over the length of his career he seems to have done more than anyone else to drive melody from popular music. Its steadily reduced presence, and the elevation of rhythm above all else, have defined pop for a while now. Where Brown led, many have followed. I realize this places me close to Generation-A parents who denounced rock and roll for deposing the “grown-up” music of Sinatra and the Mills Brothers (“In my day...”).

Something separates Brown from other innovators whom I don’t hold accountable for what they inadvertently wrought— Dylan for the still-advancing corps of self-absorbed song-poets; Hendrix for the endlessly mutating virus of metallic shredders. Once he discovered the potency of single-riff repetition, JB more or less worked it the rest of his life, till he’d refined his music down to the point of a drill bit.

Which is a roundabout way of introducing the topic at hand: the fleeting subgenre of black pop that could be termed Pre-Soul, which exhibits much of the same grit and vocal fervor as Brown.

The term Soul Music didn’t come into wide usage until roughly the latter half of the Sixties, when it was applied to R&B records on Atlantic (Aretha, Wilson Pickett) and Stax (Otis Redding, Sam & Dave), while less so Motown. Its godparents were, of course, Brown, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke and others, who sanctified Top 40 with impassioned personal styles that leapt straight from the pews.

Pre-Soul was confined to a handful of singles and a brief window of operation, roughly from 1960 to 1963, though a major example of pre-Pre-Soul, the Isley Brothers’ “Shout—Part I,” came out in 1959. Confinement, and the aggressive triumph over restraint, is a key characteristic of Pre-Soul. So many of these records find the singer actually fighting his or her way through the arrangement, working to liberate a shout that’s got to get out. It’s the dynamic so prominent in Levi Stubbs’ Four Tops vocals later in the decade. But these raw, mostly slow or midtempo sides, were Soul music’s John and Joan the Baptists, announcing what was to come.

Ike & Tina Turner reign as the king and queen of Pre-Soul, for their ’60-to-’61 singles run alone: “I Idolize You,” “It’s Gonna Work Out Fine,” and the torrid “A Fool in Love.”

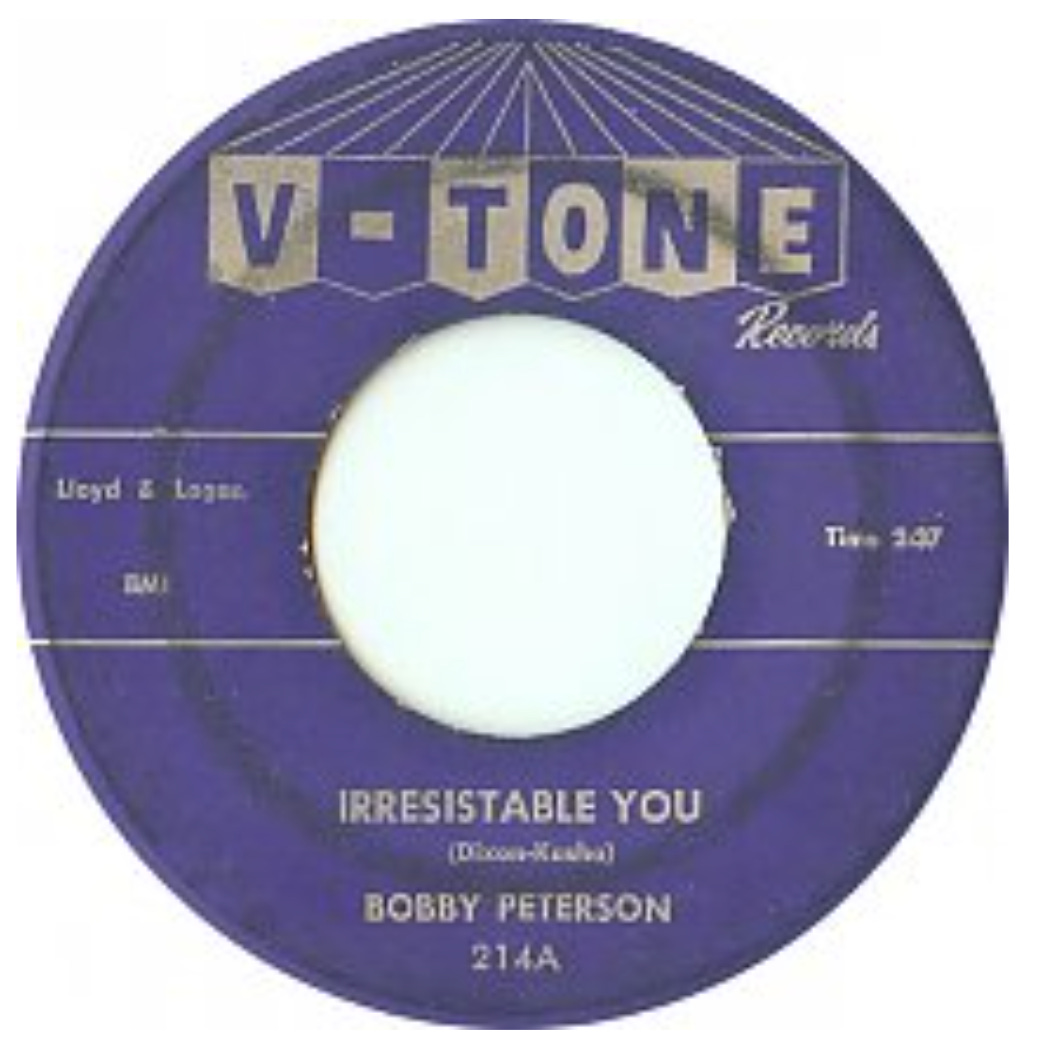

The first P-S record I brought home was “Irresistible You,” by Philly singer-pianist Bobby Peterson; Bobby Darin had the hit version in ’62, but Peterson’s was out two years earlier and got generous airplay on Bay Area radio. As the band swings and bounces, Peterson pushes the vocal like a bulldozer; behind the sax solo, the tambourine rattle and Peterson’s piano lend a quasi-New Orleans vibe that is, yeah, irresistible.

Apart from Tina’s sides, one single that set the standard for Pre-Soul females is Mary Wells’ “Bye Bye Baby” (1961). From her unaccompanied “Welll...” at the top of the record, all the way through its raucous fade, she’s boxing against the ducking, diving instrumental bed—and punching way above her class. (On a radio aircheck from the era, a DJ praises her for “wailin’ her head off”). The record is far earthier than her subsequent Smokey Robinson-penned hits. “What’s A Matter, Baby,” by the diminutive Italo-American Timi Yuro, is just as bold, with Yuro’s Etta Jamesian vocal nearly overpowering the song’s bridge.

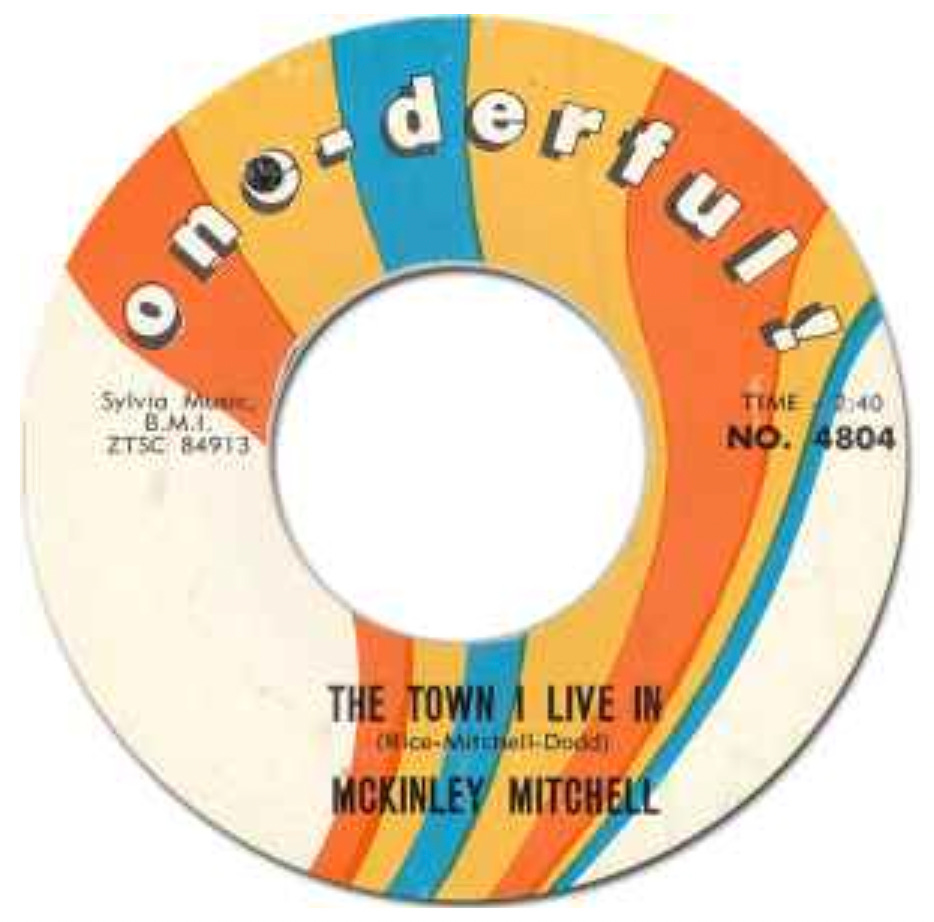

Yuro’s record is from 1962, as is McKinley Mitchell’s searing ballad, “The Town I Live In.” A stinging blues guitar lick (under-girded by a lounge-y organ) starts “Town,” then Mitchell arrives to bust down the door. He’s tortured, his raspy voice pleading for an emotional lifeline that, by the record’s end, seems forever beyond his grasp. The single was hugely popular among East L.A. Hispanics, and it was a favorite of DJ Tom Donahue as well. On “How Can I Forget” (1963), Mississippi’s Jimmy Holiday, similarly afflicted, rises to equal heights of heartbreak.

Solo Pre-Soul cats pouring their hearts out is one thing. They trudge across a desolate landscape, one littered with distant strings or far-off horns that only serve to reinforce their aloneness. In contrast, Paul Williams (of the Temptations) on “I Want a Love I Can See” and Billy Gordon (the Contours) on “Do You Love Me” each have the benefit of a support staff. That backup energy, supplementing what one Motown historian described as Williams’ “rough-edged baritone” and Gordon’s “sandpaper screams,” shoves those records across the line to classic P-S status.

Two singles that represent to me the apex of the Pre-Soul group sound deploy decidedly unfunky source material. “Que Sera Sera” made its debut in 1956, sung by Doris Day, in a Hitch- cock film, while “Zing! Went the Strings of My Heart” was widely popularized by Judy Garland in the Thirties. Day’s cheerful reading of “Que Sera Sera” bears scant resemblance to the maelstrom of sound cooked up by arranger Charlie Calello and producer Bob Crewe for High Keyes vocalist Troy Keyes (1963). He marvelously hacks his way through a dense Latinate thicket of congas, piano, horns, cowbell and trilling parade whistles, and a rasping guiro gourd. It’s easy to get lost in.

Los Angeles’ Furys started out working an R&B novelty vein much like the Coasters, but there’s nothing funny about their version of a tune the Coasters consigned to the B-side of 1958’s “Yakety Yak.” The Furys’ “Zing!” is tough stuff. It’s also interactive: lead voice Jerome Evans swaps verses and choruses with the rest of the quartet across a noisy scrim stitched together from handclaps and drumrolls. (Disclosure: I used the 45 to practice the chalypso in front of a hallway mirror in my childhood home.)

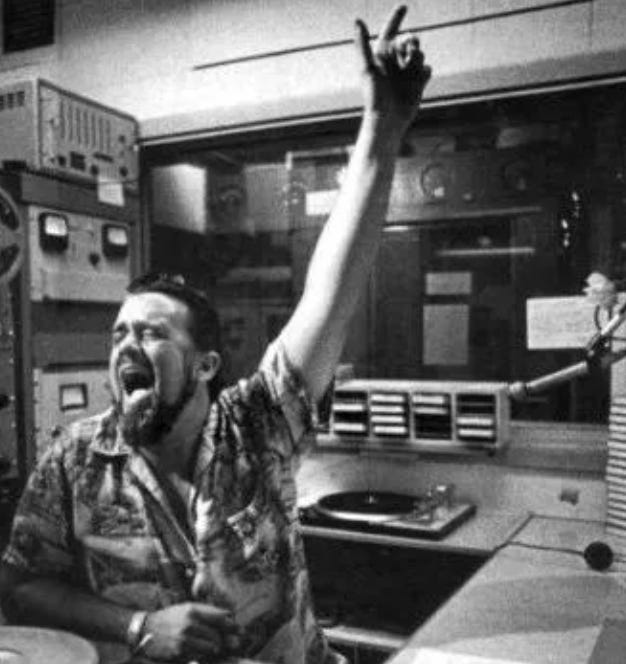

Two AM, Fillmore and Geary, San Francisco, sometime in 1967. After five hours of benign delirium inside the Fillmore Auditorium with the Grateful Dead and, if I recall, the Airplane, my friends and I emerged into a neighborhood on the edge of chaos. Cop cars and sirens, men running, cars clogging intersections. My old Dodge crawled, stopped in traffic on Fillmore St.; two scared black teenagers asked if we’d give them a lift to safety. We did. From the dashboard Wolfman Jack howled over blues records on XERB (“50,000 Watts of Soul Power”). The kids wanted to know who this raving DJ was, and disbelieved me when I told them he was white.

By the early Eighties, Wolfman was world-famous and long gone from XERB, which, rechristened XPRS, ran a vintage R&B and oldies format. The station’s playlist was deep, and cut off prob- ably around 1968. (One ’PRS jock was Jim Woods, AKA “the Vanilla Gorilla,” a finger-popping daddy who occasionally displayed a lack of familiarity with the music; he once tagged the artist on “Foxey Lady” as “the Jim Hendrix Experience.”)

It was another DJ there, Rick Ward, a packager of oldies compilations of dubious legality, who delivered my sole “I heard something on the radio so powerful I had to pull over to the side of the road” experience. One late night, driving home, in the eastbound lane of Venice Blvd. approaching Fairfax Ave., I heard Ward play an oldie I wasn’t familiar with: “I Want a Boyfriend.” Another slow-build burner, it ran on a clock-tick rhythm slashed out by hard chording, like what the Stones do on “Heart of Stone.” It was all chorus and bridge, and the female half of the duo was way out of her head in the range and emotion departments. I parked the car, dazed, and sat there: What the heck was that? I felt like the airline pilot who’s just seen a plate-shaped object pass him on the right.

Rick Ward identified the artists. They went by the names of a real-life couple that film critic Roger Ebert had pegged as “a gum-chewing waitress and a two-bit hood out on parole... two nobodies who got their pictures in the paper by robbing banks and killing people. They weren’t very good at the bank robbery part of it, but they were fairly good at killing people and absolutely first- class at getting their pictures in the paper.”

This Bonnie & Clyde cut “I Want a Boyfriend” in 1963, the peak year of Pre-Soul, and released in 1968, a year after Arthur Penn’s film starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway came out. That’s when the owner of tiny In-Sound Records—its logo spelled out in an era-appropriate psychedelic swirl—issued it and tagged the two L.A. vocalists with the historic hoodlums’ handle.

“Clyde” was Robert Jackson. “Bonnie” was Brenda Holloway. Not surprisingly, her chops led her, in 1964, to gift Motown with a hit single rightly deserving of the twin appellations “Soul” and “elegant”: “Every Little Bit Hurts.”